A recent social media trend discussed how the serving method of staple foods might impact women’s participation in family conversations. The theory suggests that the communal, all-at-once serving of rice allows for more participation, whereas the serving of hot rotis often means the women spend more time in the kitchen.

While this is an interesting connection, we still have a significant number of women and girls whose first obstacle is not the participation or the style of their meal, but the fight for the meal itself.

The global challenges of gender inequality and food insecurity do not exist in a vacuum. They are being dangerously amplified by a third, overarching crisis: climate change. Climate change acts as a powerful threat multiplier, disproportionately impacting the rural poor, and particularly women, who are on the frontlines of its effects. It deepens existing inequalities, increases women’s workloads, threatens their health and livelihoods, and erodes their already fragile food security.

Why a Gender Lens is Non-Negotiable

The impacts of climate change are not distributed equally; they are profoundly unjust. A growing body of evidence quantifies the disproportionate economic and social costs borne by women. A Food and Agriculture Organisation analysis found that a 1-degree Celsius increase in long-term average temperatures is associated with a staggering 34% reduction in the total income of female-headed households, compared to male-headed households.

The future projections are even more alarming. A joint report by UN Women and UN DESA warns that under a worst-case climate scenario, by the year 2050, an additional 158 million women and girls could be pushed into extreme poverty as a direct result of climate change. In the same scenario, the number of women and girls suffering from food insecurity is projected to increase by as many as 236 million, with 57 million (~24%) of them from Central and Southern Asia.

Existing systems of disproportionate responsibilities and ownership significantly make the situation even dire.

The Funding Reality: A Call for Smarter, Gender-Focused Investment

A Case Study: India’s National Nutrition Mission (POSHAN Abhiyaan) India’s flagship nutrition program offers a powerful lesson in the limitations of well-funded but gender-neutral approaches.

- Massive Budgets, Muted Impact: The program commands a significant budget (e.g., ₹21,960 crore, or ~USD 2.6 billion, for Saksham Anganwadi & Poshan 2.0 in 2025). However, its impact on key gendered indicators is weak.

- Worsening Outcomes for Women: Despite the spending, anaemia among women aged 15-49 increased from 53% to 57% between the last two national surveys.

- The Missing Link to Empowerment: A key critique is that POSHAN 2.0 remains isolated from schemes that build women’s economic power. Providing nutrition information is insufficient if a woman lacks the financial agency to purchase diverse foods or make decisions about household spending.

- The “Box-Ticking” Problem: Funding is often tracked in a way that looks good on paper but lacks strategic impact. For example, a large portion of India’s gender budget falls under a category where schemes must have at least 30% of their allocation for women, a mechanism that can mask a lack of true gender-transformative design.

How to Move Towards Gender-Transformative Interventions?

To move from identifying the problem to implementing solutions, it is essential that we move towards a “Gender-Transformative” approach. This approach seeks to actively challenge and shift the underlying power structures, social norms, and inequalities that perpetuate vulnerability.

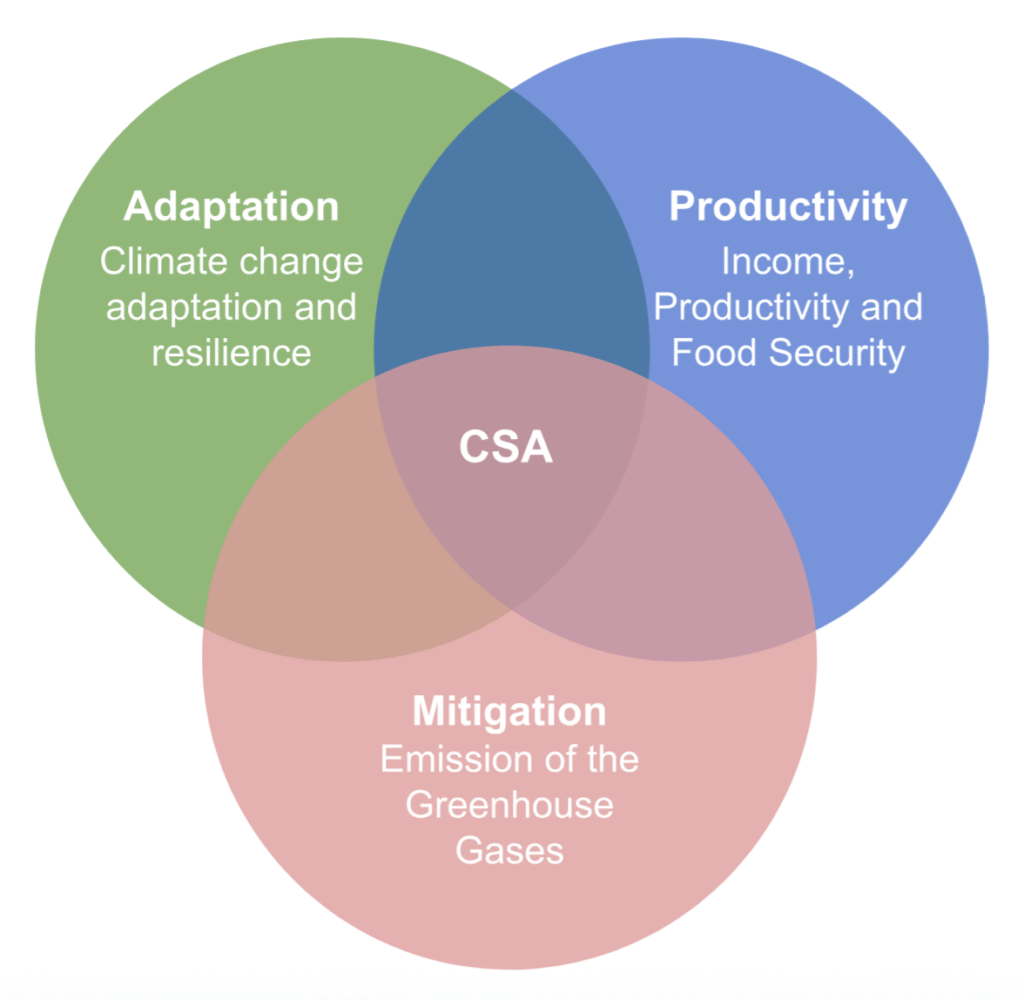

To achieve this, Gender-Transformative Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) is emerging as a leading approach.

One of the core goals of CSA initiatives is to increase efficiency and reduce labour through the introduction of new technologies. However, without a careful gender analysis, such interventions can have devastating, unintended consequences for the most vulnerable women.

Another powerful example comes from a study in India, which examined the impact of introducing mechanical threshers – a classic labour-saving technology. The study found that this innovation displaced the poor, landless women who had previously earned a significant portion of their income from manual threshing labour. Similarly, the introduction of direct rice seeders, another CSA practice, eliminated the need for manual rice transplanting, which was a critical source of wage labour and income for women in the community. While it can be quoted as a reduction in drudgerous tasks women perform, the technology primarily benefits the (often male) landowner by reducing labour costs. This ends up deepening the poverty and food insecurity of the very women who were already most marginalised.

Questions that help identify potential Gender blindness

How can we reduce such gaps? The following questions help identify potential design pitfalls that can cause gender blindness.

- Whose labour is being saved?

- Who stands to lose income or employment?

- Whose workload might be unintentionally increased?

- Does this intervention increase a woman’s decision-making power, or does it reinforce her dependency?

This requires an intersectional approach that looks beyond gender alone to consider how impacts may differ based on class, caste, land ownership, and other social identities. When a CSA intervention is likely to have negative consequences for a particular group of women, it must be paired with complementary measures – such as social protection schemes, alternative livelihood training, or targeted financial support – to mitigate the harm and ensure a just transition. Without this deliberate, gender-transformative focus, CSA risks becoming another tool that, despite its good intentions, leaves the most vulnerable women further behind.

Reading Resource:

- Climate-smart agriculture Case Studies 2021: Projects from around the world

- Women and Climate-Smart Agriculture: A Programming Guide for Eastern and Southern Africa

https://africa.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/CSA%20programme%20guide%5B53%5D.pdf

References:

- https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/2f1c3139-f85f-415c-8985-b13cc109861a

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Three-Pillars-of-Climate-Smart-Agriculture_fig10_326920644/actions#reference

- https://www.csis.org/analysis/unjust-climate-bridging-gap-women-agriculture

- https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/op-ed/2024/03/op-ed-building-womens-resilience-to-climate-driven-poverty-and-food-insecurity

- https://africa.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/CSA%20programme%20guide%5B53%5D.pdf

- https://www.impriindia.com/insights/poshan-abhiyaan-2-0-indias-nutrition/

- https://forumias.com/blog/gender-inequality-weakens-nutrition-programmes-for-indian-women/

- https://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture/en/