Why AI for Social Impact in India Is Stalling at the Policy Layer

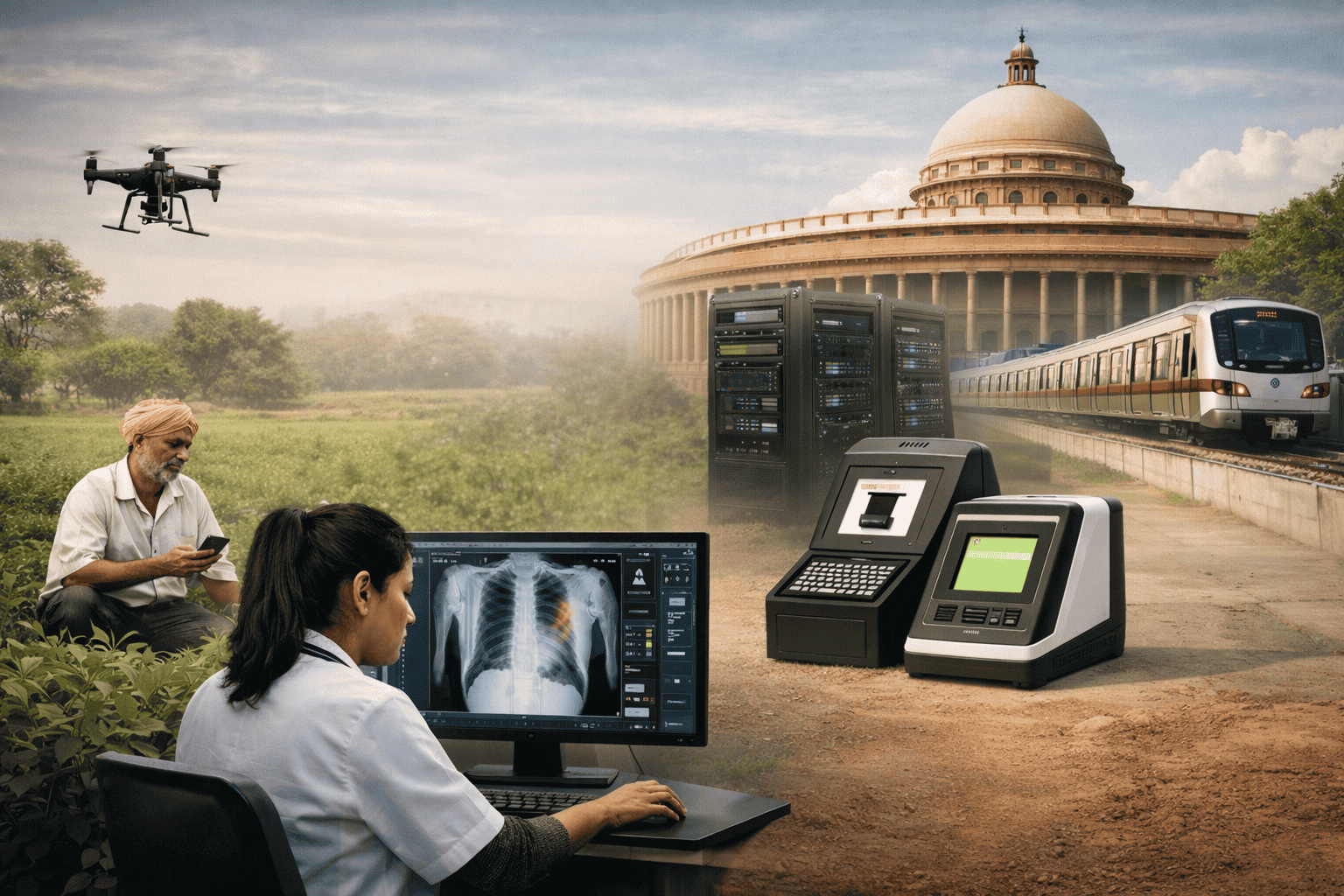

India’s development sector is experiencing a paradox. Artificial Intelligence (AI) uptake across health, education, agriculture, livelihoods, justice, and social protection is widespread and accelerating. Yet, very few of these interventions are successfully transitioning from pilots to institutionalised, large-scale public systems.

Over the last three years, India has witnessed an unprecedented expansion of AI experimentation in the development sector. This has been driven by:

- Strong state signals (IndiaAI Mission, sectoral digitisation programs)

- Philanthropic and CSR capital funding pilots

- NGOs and startups building AI tools for last-mile delivery

- Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) enabling data and identity rails

This is not a technology problem. India ranks among the top countries globally for AI talent, experimentation, and digital public infrastructure. The core reason: scaling AI is a system challenge, not a model challenge.

This piece synthesises insights from India’s AI-for-impact ecosystem to surface where and why scaling breaks down, and what this implies for policymakers, funders, and implementers seeking durable impact.

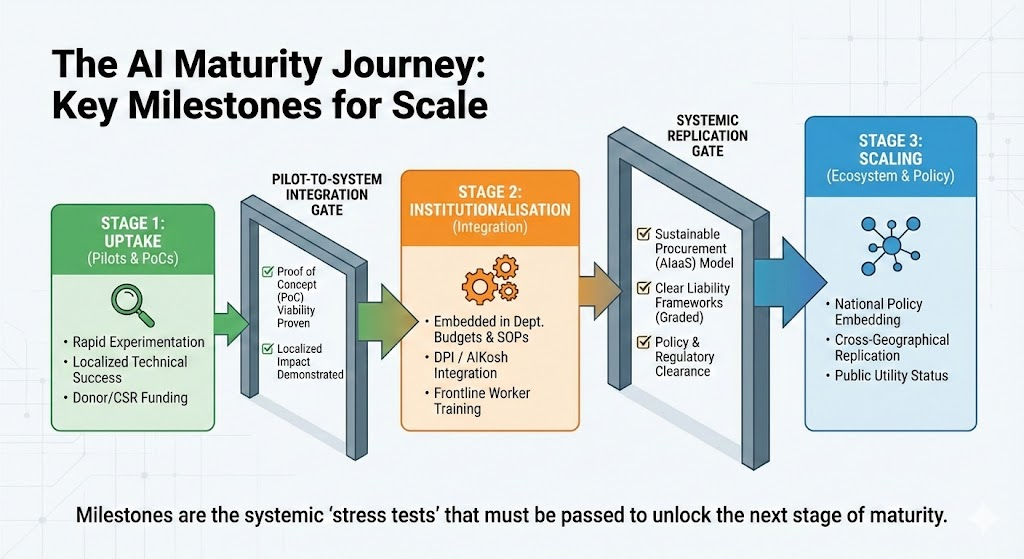

The AI Maturity Journey: Where Scale Breaks

Scaling AI in development involves key milestones from initial Uptake (Proof-of-Concept, Pilots, Demonstrating Value), moving to Institutionalisation (Integration, Policy, Governance, Capacity Building), and finally reaching Scale (Widespread Adoption, Ecosystem Building, Sustainable Impact).

Most interventions remain stuck in what practitioners increasingly describe as a “pilot graveyard.” Technically successful tools fail to cross into routine government adoption or national scale. Their journey can be described in the following “institutional gates”:

Stage 1: Uptake (Pilots and Proofs of Concept)

AI performs well here. Subsidised compute, challenge grants, and flexible partnerships enable rapid experimentation.

Stage 2: Institutionalisation (Integration and Governance)

This is where most interventions stall. Integration with government or institutional workflows, procurement systems, data governance, and frontline capacity becomes the binding constraint.

Stage 3: Scale (Policy, Budgeting, Replication)

Very few AI tools reach this stage because unresolved accountability, liability, and legitimacy concerns create a “scale ceiling.”

Cross-Sector Diagnosis: Same AI, Different Outcomes

One of the most striking findings is that the same AI capability behaves very differently across sectors, depending on regulatory posture, risk sensitivity, and institutional norms.

Consider the technology of “Computer Vision”

- In Agriculture, computer vision applied to satellite imagery for crop yield estimation is scaling rapidly. It integrates seamlessly with insurance and credit workflows because the cost of error is financial and amortized over large portfolios.

- In Healthcare, computer vision applied to X-rays for Tuberculosis (TB) detection faces immense friction. Despite high technical accuracy, these tools often fail to scale because they disrupt clinical workflows, require rigorous “clinical validation” by regulators like the CDSCO, and face resistance from medical professionals wary of liability.

To move beyond the “pilot graveyard,” we must evaluate each sector against a specific set of Readiness Anchors. These questions are designed to move the conversation from “Does the code work?” to “Can the system absorb it?”

Policy & Regulatory Posture

- Does the sector have legal frameworks such as “Safe Harbour” provisions, liability rules, and sector-specific guidelines? For instance, the “Graded Liability Framework” proposed by MeitY suggests different levels of accountability based on the risk profile of the AI, which impacts sectors differently.

Data Infrastructure & Sovereignty

- Is the data structured and accessible via APIs (like AgriStack or UPI), or is it trapped in silos? It also addresses questions of ownership: Does the citizen own their data, or is it extracted by vendors?.

Institutional & Human Capacity

- Is there a “middle-management” layer capable of procuring and managing AI, and is the frontline (e.g., ASHA workers, teachers) trained in AI-collaboration?

Procurement & Financing Reality

- How is AI bought and paid for? Does the sector’s financial framework allow for AI-as-a-Service (AIaaS) models, or is it still locked into rigid “one-time hardware buy” cycles? Traditional CAPEX models (buying hardware) often clash with the OPEX nature of AI (cloud compute, token costs). The rigidity of government procurement rules (GFR) can stifle the adoption of iterative AI solutions.

Accountability & Risk Sensitivity

- Is there a sector-specific Graded Liability framework that defines responsibility for algorithmic errors versus human error? In high-stakes sectors like Health and Justice, the tolerance for “hallucinations” or false positives is near zero. In contrast, skilling recommendations may tolerate a higher error rate.

Evidence & Legitimacy Thresholds

- What specific “proof points” does the sector require to move from pilot to policy? (e.g., gold-standard clinical trials vs. simple efficiency gains). Is it a randomized control trial (RCT), a fiscal audit, or market adoption? The mismatch between the rapid iteration of AI and the slow pace of academic or clinical validation is a major bottleneck.

What This Means for Strategy and Investment

The core insight is simple but uncomfortable:

AI for social impact in India is not failing because models are weak, but because institutions are unprepared.

For the ecosystem, this implies: a “Model-First” to “System-First” to bridge the gap between pilot success and scale, stakeholders must operationalize these four strategic imperatives.

1. Policymakers: Design Sector-Specific “Scale Highways”. A generic national policy cannot serve diverse sectors. We are moving toward distinct regulatory architectures:

2. Funders: Invest in “Absorptive Capacity”. The “Pilot Graveyard” is filled with tools that institutions couldn’t absorb. Smart capital is shifting from funding code to funding change management.

3. Implementers: Design for “Regulatory Legitimacy”. In the public sector, trust is a currency as valuable as accuracy.

4. Evaluators: need to focus on system readiness, not only accuracy metrics. An AI model with 95% accuracy in the lab can fail if the system isn’t ready to use it.

India’s ambition to use AI as a lever for inclusive development is both credible and necessary. But the next phase of progress will not come from more pilots or better models alone.

It will come from the harder work of policy design, regulatory clarity, procurement reform, and institutional capacity building.

The bottleneck is no longer innovation. It is integration and governance.